“Believe in the desperation of your sister, not me.” When Kim Go-eun delivered this line in The Price of Confession, she wasn’t just talking to her co-star—she was talking to the audience. In a career-defining interview to cine21, the actress revealed that she has moved past the phase of being “mean to herself” and is now focused on the “synergy” of female-led noir. Whether she’s cutting her hair to a near-shave or whispering through prison walls, Kim Go-eun is betting on your desperation for a real performance. And as the stats show, she never loses that bet.

From the rain-soaked, neon-lit streets of Goblin to the mud-caked, primal rituals of Exhuma, Kim has established herself as a master of sensory acting (sense memory or sense work). She is unafraid of the ugly, the raw, and the exhausting. When we look back at the last decade of Korean entertainment, her face is often the anchor for its most visually ambitious moments.

We rounded up the definitive collection of her standout scenes—moments where cinematography, lighting, and performance collided to create pure visual energy.

15 Best Standout Scenes of Kim Go-eun

Guardian: The Lonely and Great God (Goblin)

“The Pier Summoning”

In the scene that defined the visual language of fantasy romance for a generation, a lonely high schooler, Ji Eun-tak, sits alone on a rocky pier on her nineteenth birthday. The scene is initially graded in “loneliness”—a desaturated, biting palette of steel greys, cold blues, and the white foam of a crashing winter ocean. You can practically feel the salt spray and the biting wind cutting through the screen.

Director Lee Eung-bok orchestrates a thermal shock. The cinematography undergoes an instant transition from cold to warm. As the Goblin (Gong Yoo) materializes, the lighting shifts to a deep, protective amber. The smoke from the match does not dissipate according to normal physics; it lingers, coiling in the air, physically bridging the gap between the mortal and immortal planes. Kim Go-eun’s performance here is one of scale. Shot in a wide angle, she appears small and fragile against the vast, dark ocean, until the Goblin enters the frame, vertically dominating the space and establishing his role as her shield. It is a masterclass in using weather and light to tell a love story.

Little Women

“The Closed Room”

If Goblin is about vastness, Little Women is about suffocation. The horror of this scene lies entirely in its texture. When In-joo enters the secret room, the screen is bathed in the toxic, violet-blue luminescence of the “Blue Orchid.” In a drama defined by the drab, beige palette of poverty, this sudden burst of saturated color signals immediate danger.

The camera movement here creates a sense of vertigo. It zooms past In-joo into a dollhouse, revealing a perfect, miniature 1:1 replica of the murder scene she is currently standing in. Kim Go-eun sells the horror of this “Russian Nesting Doll” moment not with a scream, but with a terrifying stillness. Her eyes track the miniature details—the red heels, the fur coat—with a trembling focus. It is the visual realization that she is not a protagonist in her own life, but merely a plastic toy in a rich person’s game. The scene creates a feeling of claustrophobia that lingers for the rest of the episode.

Exhuma

“The Daesal Gut”

This is perhaps the most iconic moment in Korean cinema history. Director Jang Jae-hyun abandons the tripod for a frantic, handheld orbit that mirrors the chaotic drumming of the shamanistic ritual. The scene rejects CGI in favor of visceral, practical effects. The smoke choking the screen is real burning wood; the sweat on Kim’s face is real exhaustion.

Hwa-rim (Kim Go-eun) performs the Daesal Gut to ward off evil, slashing at pig carcasses with heavy blades. The sound design is crucial here—it amplifies the wet, sickening thwack of steel hitting meat, grounding the supernatural in a fleshy, bloody reality. The visual brilliance lies in the costume contrast: Kim is clad in a high-fashion trench coat and Converse sneakers while performing an ancient, primitive rite. This creates a jarring “Modern Shaman” vibe aesthetic—a clash of the prehistoric and the contemporary that she navigates with the precision of a surgeon and the grace of a dancer.

The King: Eternal Monarch

“The Bloody Salute”

A collision of genres in a single frame. A blood-soaked Tae-eul reunites with Lee Gon after a brutal street battle. visually, the screen is split between two worlds: Tae-eul is dressed in the gritty, realistic grime of a detective noir—flannel shirt, realistic blood splatter, matted hair—while Lee Gon stands in the pristine, gold-and-white uniform of a high-fantasy prince.

Most performers would lean into the romance of the rescue, but Kim Go-eun leans into the trauma. The camera locks on her hands, which are shaking uncontrollably from the adrenaline dump of the fight. Her stare is not one of love, but of combat shock. By focusing on these micro-tremors and the “thousand-yard stare,” she grounds a scene involving parallel universes and cavalry charges in the very real physical toll of violence. It turns a glossy romance moment into something gritty and substantial.

Yumi’s Cells

“The Cafe Breakup”

Breakup scenes are a dime a dozen, but this one utilizes space to devastating effect. The director uses the physical architecture of the cafe—window frames, table edges, and pillars—to visually cut the screen in half, separating Yumi and Woong before they even speak a word. The depth of field is shallow, isolating them in their own private bubbles of misery.

The true genius, however, lies in the mixed-media format. We see Kim Go-eun’s stoic, composed face in the live-action world—a mask of adult maturity. Simultaneously, the show cuts to her animated “Inner World,” where her primary Cell is drowning in a literal flood of tears, clinging to a raft. It is the perfect visual metaphor for the universal human experience of “holding it together.” The contrast between Kim’s still, silent face and the chaotic, animated flood creates a heartbreaking dissonance that dialogue alone could never achieve.

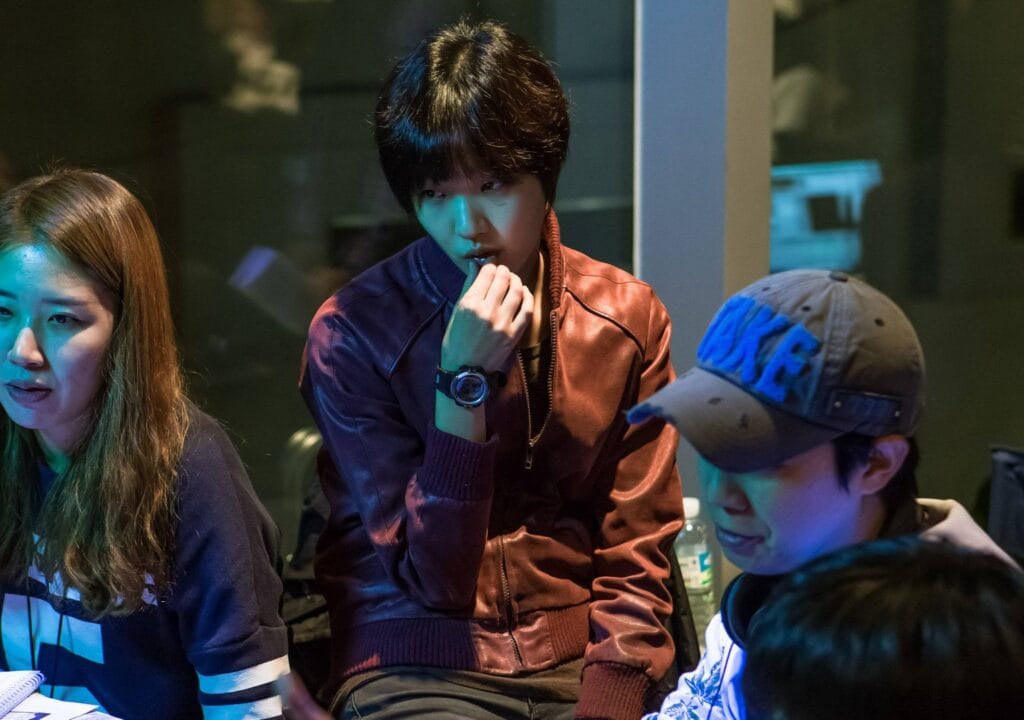

The Price of Confession

“The Wall Whisper”

In a drama that thrives on noir aesthetics, this scene relies on what you cannot see. Mo Eun (Kim Go-eun) offers a deal to Yun-su through the crack in a solitary confinement wall. The visual texture is defined by concrete—grey, rough, and impenetrable. The lighting is low-key, casting deep shadows that obscure Mo Eun’s face, turning her into a disembodied voice.

Kim drops her voice an octave here, shedding her usual warmth for a chilling, “Witch”-like whisper that echoes off the stone. The wall separates the two women physically, but the voice bridges the gap. The sound design enhances the reverb, making her offer sound less like a human negotiation and more like a devil’s pact filtering through the cracks of hell. It is a testament to her vocal control that she can dominate a scene without fully being in the frame.

Coin Locker Girl (Chinatown)

“The Fluorescent Noir”

This film stripped away all glamour, leaving only the texture of rust and blood. The scene where Il-young sits in the subway locker station is bathed in a sickly, fluorescent green light. In Asian noir cinema, this specific hue is often used to signify corruption, sickness, and moral decay. It makes the air look humid and dirty, as if the screen itself is sweating.

Kim Go-eun employs a “matte eye” technique here. Unlike the sparkling, reflective eyes she uses in Goblin, her eyes in this scene absorb the light. She sits perfectly still, blending into the metal lockers behind her. She visually communicates that she is not a person, but merely another piece of discarded luggage stored in a locker. It is a haunting image of dehumanization achieved through color grading and stillness.

Tune in for Love

“The Window Reflection”

Glass is the third main character in this film. For two hours, windows serve as barriers, constantly separating Mi-soo and Hyun-woo as they miss each other through the years. In the final emotional punch, the lighting director shifts the angle of the sun so that the bakery glass becomes transparent rather than reflective.

The camera intentionally overexposes the shot. The sunlight blows out the highlights, creating a soft, hazy “bloom” or halo effect around Kim Go-eun as she smiles. This overexposure mimics the way a blinding, happy memory feels in the human mind—warm, fuzzy, and radiant. It visually signals that the barrier is gone and their timing has finally aligned.

Hero

“The Courtroom Song”

A musical film requires a different kind of energy, and the courtroom scene in Hero is a study in vocal texture. As Seol-hee, Kim Go-eun does not sing a polished, Broadway-style number. Instead, she performs a “guttural aria.”

The camera stays in a tight close-up on her face, capturing every micro-expression of despair. She sings through tears, allowing her voice to crack and break. The “imperfection” of the singing is the point—it is a scream of patriotism and grief disguised as a melody. The lighting is stark and high-contrast, casting her in the harsh judgment of the court, but her performance pushes back against the frame. It is a moment where audio and visual agony merge perfectly.

Memories of the Sword

“The Tea Tasting”

In a martial arts movie filled with wire-work and sword fights, the most tense scene is one of absolute stillness. Seol-hee performs a blind tea tasting, and the cinematographer switches to a macro lens.

We see extreme close-ups of the tea pouring, the steam rising, and the twitch of an ear. The visual language shifts from action to sensory isolation. Kim Go-eun conveys the “heightened senses” of a warrior not through movement, but through intense, frozen concentration. The shallow depth of field blurs out the world, forcing the audience to focus on the liquid texture of the tea and the silence of the room. It is a visual representation of the calm before the strike.

Monster

“The Tantrum”

If her other roles are about control, Monster is about the loss of it. Playing a character with a developmental disability and uncontrollable rage, Kim Go-eun creates a scene of feral energy. When her character Bok-soon loses her temper, she throws herself onto the ground, screaming and thrashing.

The camera framing is chaotic, refusing to keep her in the center, mirroring her unhinged mental state. She abandons all vanity, contorting her face and body into shapes that are uncomfortable to watch. It is a performance of ugly energy, raw and unfiltered, proving early in her career that she prioritized character truth over aesthetic beauty.

Cheese in the Trap

“The Drunk Fall”

Physical comedy is a form of kinetic storytelling, and this scene is a masterclass in ragdoll physics. When Hong Seol gets drunk, Kim Go-eun allows her body to go completely limp. She headbutts the table and slides off the bench with the fluidity of water.

The visual prop here is her hair. Her signature “poodle perm” becomes a character itself, creating a chaotic, frizzy halo around her head that matches her messy internal state. The director shoots this from a low angle, emphasizing the disorientation of intoxication. It is a moment of levity that relies entirely on her physical commitment to looking foolish.

Sunset in My Hometown

“The Golden Hour Slap”

Lighting dictates emotion. In the confrontation scene between Sun-mi and the protagonist, the sun is setting, casting the world in the “Golden Hour”—a time usually reserved for romance. However, the action is one of frustration.

The contrast between the romantic, soft-focus backlit lighting and the sharp, stinging reality of the dialogue creates a visual irony. Kim Go-eun plays the scene with a grounded frustration, her silhouette cut sharply against the dying light. It visually represents the fading of a childhood dream and the harsh reality of adulthood.

Canola

“The Smoking Shadow”

A small, quiet moment that speaks volumes. Kim Go-eun, playing a troubled youth, smokes a cigarette in the shadows while her grandmother looks for her. The lighting is “chiaroscuro”—high contrast between light and dark.

She stands in the darkness, the only light coming from the cherry of the cigarette. The smoke curls up into the light, revealing her face in fragments. It is a visual metaphor for her fractured identity and the secrets she is keeping. The way she holds the cigarette—protective, habitual—adds a layer of gritty texture to a film that is otherwise filled with bright Jeju Island scenery.

A Muse (Eungyo)

“The Porch Sunlight”

The film that started it all. The scene where Eungyo sleeps on the wooden chair in the garden is a study in tactile cinematography. The camera uses soft-focus lenses and natural sunlight to create a dreamlike atmosphere.

It isn’t just bright; it is hazy. The camera lingers on textures—the grain of the wood, the fabric of her white shirt, the sweat on her skin. It creates a sensory experience where the viewer can almost feel the humid summer heat and the stillness of the afternoon. Kim Go-eun is perfectly still, yet the way the light dances across her face creates a dynamic image of innocence and desire.

FINAL THOUGHTS

Kim Go-eun is often described as having a face that is a “blank canvas,” but that definition diminishes the active nature of her work. She is not a canvas; she is a prism.

A canvas simply holds paint. A prism takes light and bends it, refracts it, and separates it into a spectrum of colors. Whether she is embodying the frantic energy of a shaman in Exhuma or the suffocating stillness of a poverty-stricken accountant in Little Women, she changes the physics of the scenes she inhabits.

In an industry often obsessed with pristine, high-definition perfection, Kim Go-eun is unafraid of the messy, the gritty, and the granular. She allows her voice to crack. She allows her face to contort. She allows the lighting to swallow her whole. That fearlessness—the willingness to surrender to the visual language of the film rather than fight for the spotlight—is what makes her the most visually compelling actress working today.

BONUS: The Auditory Texture of Grief

We discussed the “guttural aria” in Hero. To truly understand the sensory physics of Kim Go-eun’s voice—how she allows it to crack, break, and tremble with imperfect, raw emotion—watch this full performance of “Your Majesty, I Remember.”

Notice how the camera stays in a tight close-up (a sensory isolation technique), forcing you to witness every micro-expression of pain.

Leave a Comment